| A 34 year-old woman presented with slowly progressive ataxia and slurred speech since childhood. Examination showed truncal ataxia with dysmetria on finger-to-nose and heel-to-shin testing. Two brothers were similarly affected. |

![]()

![]()

![]()

![]()

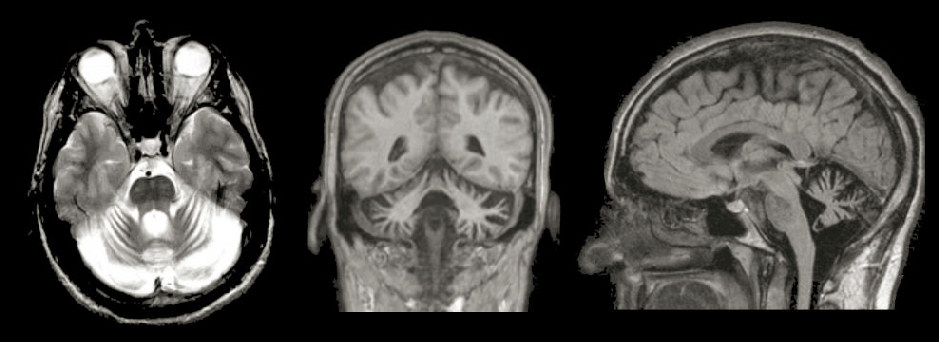

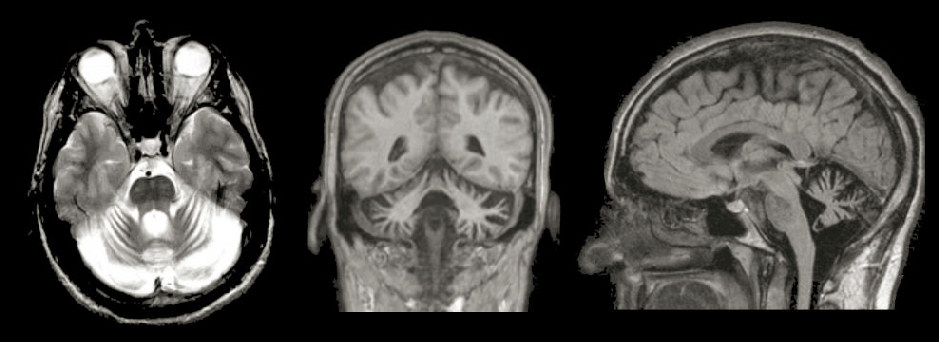

| Cerebellar Degeneration: (Left) T2-weighted axial MRI; (Middle) T1-weighted

coronal MRI;

(Right) T1-weighted sagittal MRI. In all the scans, note the severe atrophy of the cerebellum.

In contrast, the brainstem (midbrain, pons and medulla) is

normal in size. When the cerebellum atrophies, the

surrounding cisterns and fourth ventricle undergo a compensatory

enlargement (a type of de facto "hydrocephalus ex vacuo"). Marked atrophy of the cerebellum is most often associated with genetic conditions, although chronic, severe alcohol intake as well as some paraneoplastic syndromes can result in cerebellar atrophy. The nomenclature of genetic disorders associated with cerebellar atrophy is complex. Most are classified by the chromosomal location and pattern of inheritance. In many, a specific gene mutation or defective protein has been found. In the past, these disorders were referred to as cerebellar degeneration, spinocerebellar degeneration and olivopontocerebellar atrophy (OPCA) depending on whether the cerebellum, spinal cord, brainstem, or a combination of the above were affected. In this case, the patient was diagnosed with adult onset hexosaminidase A deficiency (Late-onset Tay-Sachs disease), based on enzyme testing and gene mutation analysis. |

Revised

11/30/06

Copyrighted 2006. David C Preston